We call what we do Rapid Software Testing.

Why do we test? We test to develop a comprehensive understanding of the product and the risks around it. We test to find problems that threaten the value of the product, or that threaten the on-time, successful completion of any kind of development work. We test to help the business, managers, and developers decide whether the product they’ve got is the product they want.

Above all, we test because it is the responsible thing to do. We have a duty of care toward our teams, our organizations, our customers, and society itself. Releasing poorly tested software would be a breach of that duty.

Rapid Software Testing (RST) is all about that. It is a responsible approach to software testing, centered around people who do testing and people who need it done. It is a methodology (in the sense of “a system of methods”) that embraces tools (aka “automation”) but emphasizes the role of skilled technical personnel who guide and drive the process.

The essence of this methodology lies in its humanism (we foster responsibility and resilience by putting the methodology under the control of each practitioner), its ontology (how we organize and define the various priorities, ideas, activities, and other elements of testing), and its heuristics (fallible methods of solving a problem). In RST, we’re not afraid of learning, applying, and discussing words like “ontology” or “heuristics”. For us, words are important tools we use to help us develop our expertise and to describe and explain our work.

Rather than being a set of templates and rules, RST is a mindset and a skill set. It is a way to understand testing; it is a set of things a tester knows how to do; and it includes approaches to effective leadership in testing.

What We Mean By Rapid

We are not talking about typing or clicking faster. We are talking about better test strategy. This means basically nine things:

- Take control of your own work. Unless you are under the direct supervision of someone who is responsible for your work, you must not blindly follow any instruction or process. That means whatever practices you use, and however you coordinate with other processes on the project, decide that for yourself. Don’t base your testing on test cases you don’t understand. If you don’t understand something, study it until you do, stop doing it, or advise your clients that you are working blindly.

- Stop doing things that aren’t helping. It’s hard to say which activities are really a waste of time and which aren’t, but here’s a golden rule: if you think you are doing something that is a waste of time, stop doing it.

- Embrace exploration and experimentation. Part of doing good testing rapidly is to learn quickly about the product, and that requires more than just reading a spec or repurposing an old test case. You must dive in and interact with the product. This helps you build a mental model of it more quickly.

- Focus on product risk. One size of testing does not fit all. Do deeper testing where it is needed, and do shallow testing or no testing at all when potential product risk is low.

- Use lightweight, flexible heuristics to guide your work. The RST Methodology includes many heuristic models designed to help structure your work. These models are concise, light, and can be used to support any level of testing from spontaneous and informal testing to deliberative and formalized. They are at all times under your control.

- Use the most concise form of documentation that solves the problem. Documentation can be a huge drag on any project. It is difficult to create and difficult to maintain. Either avoid it, or use the lightest form of documentation that communicates what is needed to the specific people who need it.

- Use tools to speed up the work. Testers do not necessarily need to write code, but they do need powerful tools. Whether you create the tools yourself or enlist the help of others, you can apply tools, including automated checking, to all aspects of the testing process

- Explain your testing and its value. When you can explain the importance of your testing clearly and quickly with a focus on value, your clients and teammates will perceive that your time is well spent, and therefore sufficiently rapid.

- Grow your skills so that you can do all of the above. We offer no pill you can swallow that allows you to do these things. But we do show you how to grow your skills, and in what specific directions to grow them. By developing judgment and a wide knowledge of different techniques, tools, and processes, you can choose a fast way to test that still addresses all the business needs.

Want details?

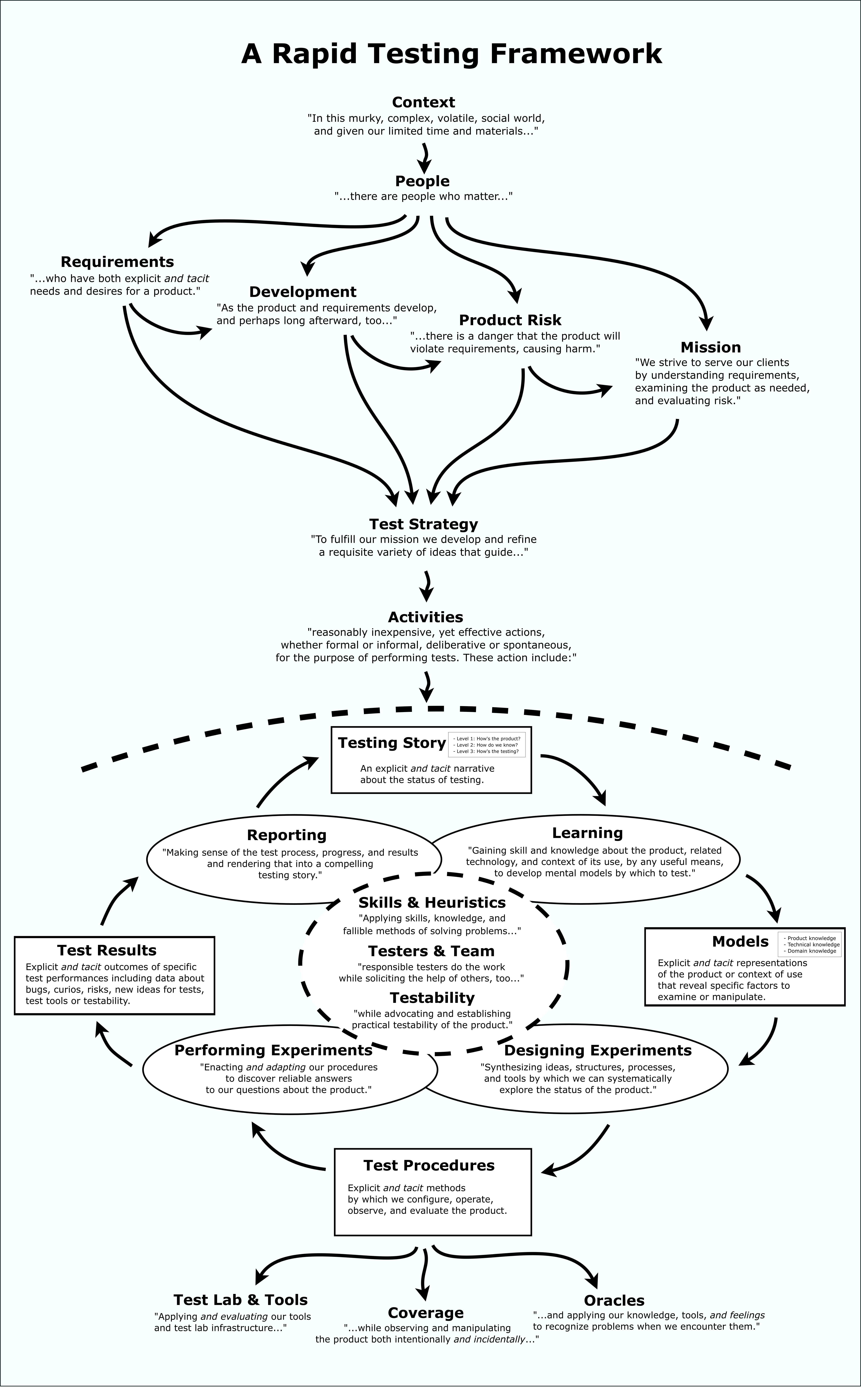

Here’s a roadmap of many of the elements of RST:

Some of the reference documents that express RST can be found here.

What Are the Foundations of RST?

RST is strongly influenced by the approach to engineering and science promoted in the works of Gerald M. Weinberg, Cem Kaner, and Billy Vaughan Koen, as well as sociologist Harry Collins, family therapist Virginia Satir, and Nobel laureates Herbert Simon, Richard Feynman, and Daniel Kahneman. If you admire their work, you will find much that resonates in the methodology and classroom experiences that we provide.

RST is also based on and related to Lessons Learned in Software Testing: A Context-Driven Approach, by Cem Kaner, James Bach, and Bret Pettichord. as well as the self-education and independent thinking approach to life depicted in James’ book, Secrets of a Buccaneer-Scholar.

Below are the specific premises of the RST, writing by James Bach and Michael Bolton. Everything in the methodology derives in some way from this foundation. These premises come from our experience, study, and discussions over a period of decades.

- Software projects and products are relationships between people, who are creatures both of emotion and rational thought. Yes, there are technical, physical, and logical elements as well, and those elements are very substantial. But software development is dominated by human aspects: politics, emotions, psychology, perception, and cognition. A project manager may declare that any given technical problem is not a problem at all for the business. Users may demand features they will never use. Your fabulous work may be rejected because the programmer doesn’t like you. Sufficiently fast performance for a novice user may be unacceptable to an experienced user. Quality is always value to some person who matters. Product quality is a relationship between a product and people, never an attribute that can be isolated from a human context.

- Each project occurs under conditions of uncertainty and time pressure. Some degree of confusion, complexity, volatility, and urgency besets each project. The confusion may be crippling, the complexity overwhelming, the volatility shocking, and the urgency desperate. There are simple reasons for this: novelty, ambition and economy. Every software project is an attempt to produce something new, in order to solve a problem. People in software development are eager to solve these problems. At the same time, they often try to do a whole lot more than they can comfortably do with the resources they have. This is not any kind of moral fault of humans. Rather, it’s a consequence of the so-called “Red Queen” effect from evolutionary theory: you must run as fast as you can just to stay in the same place. If your organization doesn’t run with the risk, your competitors will—and eventually you will be working for them, or not working at all.

- Despite our best hopes and intentions, some degree of inexperience, carelessness, and incompetence is normal. This premise is easy to verify. Start by taking an honest look at yourself. Do you have all of the knowledge and experience you need to work in an unfamiliar domain, or with an unfamiliar product? Have you ever made a spelling mistake that you didn’t catch? Which testing textbooks have you read carefully? How many academic papers have you pored over? Are you up to speed on set theory, graph theory, and combinatorics? Are you fluent in at least one programming language? Could you sit down right now and use a de Bruijn sequence to optimize your test data? Would you know when to avoid using it? Are you thoroughly familiar with all the technologies being used in the product you are testing? Probably not—and that’s okay. It is the nature of innovative software development work to stretch the limits of even the most competent people. Other methodologies seem to assume that everyone can and will do the right thing at the right time. We find that incredible. Any methodology that ignores human fallibility is a fantasy. By saying that human fallibility is normal, we’re not trying to defend it or apologize for it, but we are pointing out that we must expect to encounter it in ourselves and in others, to deal with it compassionately, and make the most of our opportunities to learn our craft and build our skills.

- A test is an activity; it is performance, not artifacts. Most testers will casually say that they “write tests” or that they “create test cases.” That’s fine, as far as it goes. That means they have conceived of ideas, data, procedures, and perhaps programs that automate some task or another; and they may have represented those ideas in writing or in program code. Trouble occurs when any of those things is confused with the ideas they represent, and when the representations become confused with actually testing the product. This is a fallacy called reification, the error of treating abstractions as though they were things. Until some tester engages with the product, observes it and interprets those observations, no testing has occurred. Even if you write a completely automatic checking process, the results of that process must be reviewed and interpreted by a responsible person.

- Testing’s purpose is to discover the status of the product and any threats to its value, so that our clients can make informed decisions about it. There are people that have other purposes in mind when they use the word “test.” For some, testing may be a ritual of checking that basic functions appear to work. This is not our view. We are on the hunt for important problems. We seek a comprehensive understanding of the product. We do this in support of the needs of our clients, whoever they are. The level of testing necessary to serve our clients will vary. In some cases the testing will be more formal and simple, in other cases, informal and elaborate. In all cases, testers are suppliers of vital information about the product to those who must make decisions about it. Testers light the way.

- We commit to performing credible, cost-effective testing, and we will inform our clients of anything that threatens that commitment. Rapid Testing seeks the fastest, least expensive testing that completely fulfills the mission of testing. We should not suggest a million dollar test when a 10 dollar test will do the job. It’s not enough that we test well; we must test well given the limitations of the project. Furthermore, when we are under some constraint that may prevent us from doing a good job, a tester must work with the client to resolve those problems. Whatever we do, we must be ready to justify and explain it.

- We do not knowingly or negligently mislead our clients and colleagues. This ethical premise drives a lot of the structure of Rapid Software Testing. Testers are frequently the target of well-meaning but unreasonable or ignorant requests by their clients. We may be asked to suppress bad news, to create test documentation that we have no intention of using, or to produce invalid metrics to measure progress. We must politely but firmly resist such requests unless, in our judgment, they serve the better interests of our clients. At minimum we must advise our clients of the impact of any task or mode of working that prevents us from testing, or creates a false impression of the testing.

- Testers accept responsibility for the quality of their work, although they cannot control the quality of the product. Testing requires many interlocking skills. Testing is an engineering activity requiring considerable design work to conceive and perform. Like many other highly cognitive jobs, such as investigative reporting, piloting an airplane, or programming, it is difficult for anyone not actually doing the work to supervise it effectively. Therefore, testers must not abdicate responsibility for their own work. By the same token, we cannot accept responsibility for the quality of the product itself, since it is not within our span of control. Only programmers and their management control that. Sometimes testing is called “QA.” If so, think of it as quality assistance, not quality assurance.

The Evolution of RST

The genesis of Rapid Software Testing was in James Bach’s experiences running testing teams at Apple Computer and Borland International, going back to 1987. He was looking for the essence of testing, and not finding it in any of the standards or books of the time. Then he received important clues from the work of Ed Yourdon, Tom DeMarco, Tim Lister, and Jerry Weinberg. They pushed him to consider general systems thinking, and opened his mind to the key role of psychology in engineering. Then in the mid-90’s, during an all-night conversation at a testing conference in San Francisco, Cem Kaner urged him to explore cognitive psychology and epistemology. These fields provided the organizing framework of James’ emerging methodology.

The first talk James ever gave about his approach to testing was called something like Dynamic Software Quality Assurance, for Apple University in 1990. He was talking about heuristics and systems thinking but though perhaps not in those words.

The first major conference talk James gave was called The Persistence of Ad Hoc Testing, in 1993. He was talking about the extraordinary value of exploratory testing, although he would not start using that term until later in the year.

The first public version of James’ testing methodology was embodied in a class called Market-Driven Software Testing, in 1995. He then created a class on risk-based testing, as well as the industry’s first exploratory testing class. In 2001, he combined these classes and began to formalize the methodology, renaming the class to Rapid Software Testing.

In 2004, Michael Bolton brought his experience as a developer, tester, documenter, and program manager to the class, adding new exercises, puzzles, and themes. Michael’s work in commercial and financial services software added and influenced ideas on the role of formality and documentation, and in 2006 he became a co-author of the class and the methodology. Over the years, he helped to refine RST, sharpening the vocabulary, and introducing the crucial distinction between checking—a part of testing that can in principle be done by machinery—and testing—which requires both the explicit and tacit knowledge of the tester.

Paul Holland (from embedded systems and telecommunications), Huib Schoots (financial services), and Griffin Jones (medical devices and other regulated domains) each brought their ideas, experiences, and teaching styles into the mix. Each one of our instructors benefits from the work of the others, and each teaches his own personal variant of RST.

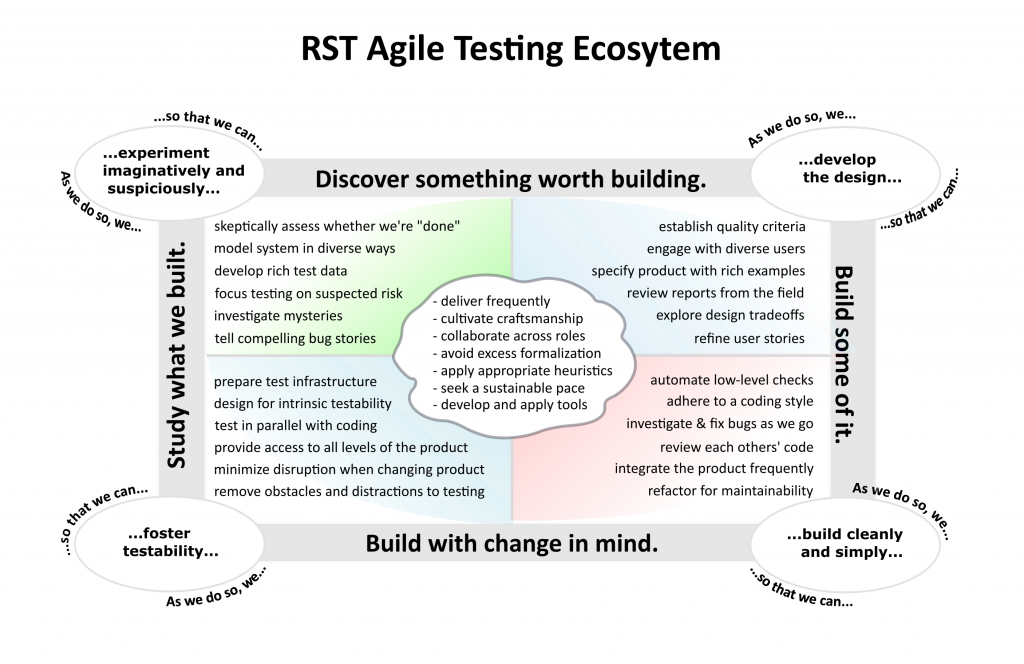

RST historically was focused on testing and testers. But we have recently refocused it a little because a lot of people who do testing are either not called testers or do other things besides testing. Our clients, these days, need to know how RST integrates with Agile and DevOps

Here is our Agile Rapid Testing Grid which helps us explain that:

What the Methodology Is Compatible With

RST is a context-driven methodology. This means the our classes are not specifically about testing in an Agile, DevOps, Lean, Waterfall, or regulated context; nor does it incorporate any specific testing tool you might use to simulate users or support any other aspect of testing. But we do help you apply these things in testing by putting you in control of the process, so that you solve the problems that actually exist in your context.

The key issue is responsibility. As a tester, responsibility means making independent professional judgments to apply practices and tools to uncover every important problem on your particular project. Responsibility means doing deep testing when project and product risk warrant it.

Applying some practice such as “unit testing” or “behavior-driven development” responsibly means choosing it when it fits your context, and not because you heard that Facebook and Google do it, or because you are ordered to do it.

Using automation responsibly includes considering approaches outside of automation when they are more effective, more efficient, or when they address problems that automation ignores.

Responsibility means that when you say “probably nothing will go badly wrong” you are not just guessing.

RST does not tell you what to do. It is instead a framework for responsible and literate consideration of what to do. The instructors of RST have experience with a wide range of contexts, and can help you customize the material to fit your needs. So, we have lots of ideas for how to apply automation to testing, or how to test well in a documentation-heavy project.

There is one thing in particular that RST methodology is not compatible with: fake testing. Yes, there are some organizations that maximize paperwork on purpose and encourage shallow test scripts that they know rarely find bugs. “Factory-style” testing often amounts to fake testing, because it looks reasonable on its face, despite failing to achieve its apparent purpose. Some companies—large testing outsourcing companies are famous for this—even do that is a business model to maximize billable hours. Such companies don’t want to test more efficiently, because that would reduce their billable hours. They want to look productive to people who don’t understand deep testing. If you work for such a company, your boss will be very annoyed with you if you attend an RST class. It will cause you to ask uncomfortable questions.

Here are some additional details about how RST compares to some other popular methodologies of testing out there.

That’s a start. There’s much more to learn about RST.